News & Blog

Galloping Through Time: Equestrian Subjects in Indian Academic Realism

Indian Academic Realism, nurtured in colonial art institutions such as the Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay and the Government School of Art in Calcutta, brought a new focus on anatomical precision, naturalistic light, and historical storytelling to the Indian art scene of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Amidst the favored subjects of mythology, portraiture, and nationalist narratives, horses and equestrian themes occasionally emerged — rare but resonant, imbued with cultural symbolism and technical mastery.

In Indian tradition, horses had long symbolized nobility, divine strength, and martial prowess, featuring prominently from Mughal miniatures to Rajput murals. However, it was under the aegis of Academic Realism that equestrian imagery achieved an unprecedented fidelity to anatomical form and dynamic movement, aligning Indian depictions with global academic standards while retaining cultural specificity.

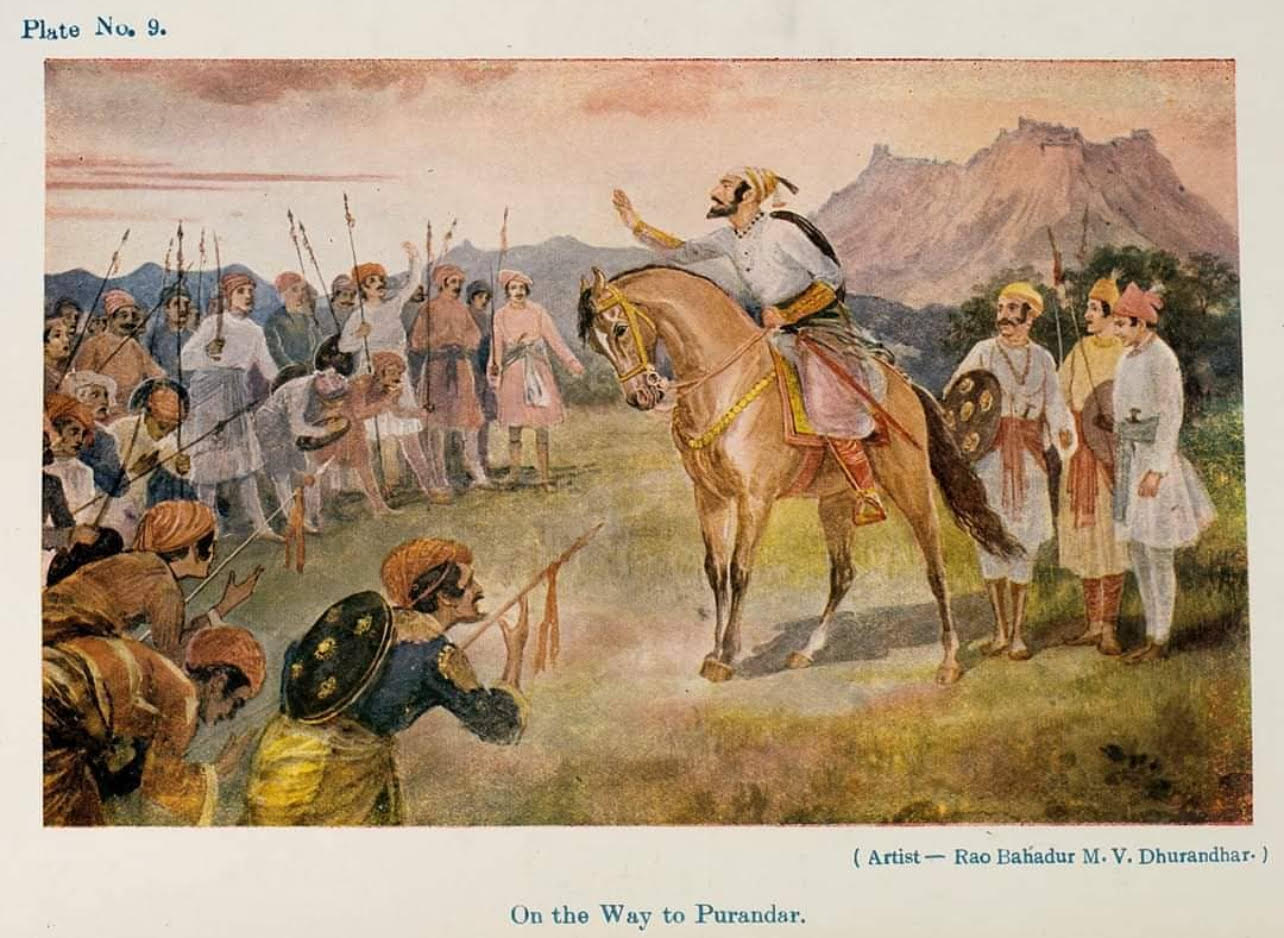

Foremost among these academic painters was M.V. Dhurandhar (1867–1944). His painting Shivaji Crossing the Sahyadri captures the Maratha hero mounted atop a spirited steed, painted with rigorous anatomical detail and theatrical dynamism. The horse, not merely a background element, becomes an extension of Shivaji’s valor, its galloping energy symbolic of the spirit of resistance. Dhurandhar’s sketches of cavalry units, some preserved in the CSMVS, Mumbai, further showcase his observational precision.

Another towering figure, Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906), incorporated horses into mythological and royal tableaux. In his celebrated Krishna and Arjuna on the Chariot, the charging horses embody divine will and cosmic urgency. His royal commissions, depicting princes astride grand horses, cemented the association between equine imagery and sovereign authority.

Artists such as Atul Bose (1898–1977) and J.P. Gangooly (1886–1953), though primarily portraitists and cityscape painters, also explored equestrian subjects. Bose’s now-rare Calcutta Horse Parade sketches and Gangooly’s Carriage Horse in Kolkata Monsoon exhibit a quieter, urban realism — horses integrated into the evolving modern life of Indian cities.

The roots of these traditions, however, trace back to the late Company School artists, notably Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya, whose Portrait of a Mounted Sikh Nobleman blends Mughal grandeur with European modeling techniques, signaling the early evolution of realistic equine representation in Indian art.

Unlike the West, where equestrian portraiture often stood as a distinct and celebrated genre, Indian academic realists typically embedded horses within broader narrative frameworks — battles, mythologies, and regal life — using them as potent symbols of cultural identity and historical memory.

Today, purely equestrian works from this period remain rare, with many housed in private collections or under-documented in museum archives. Their scarcity enhances their significance: they offer not only insights into a technical and aesthetic evolution but also a galloping reminder of a time when Indian art negotiated tradition and modernity atop powerful, spirited steeds.