News & Blog

V. R. Chitra and the Revival of Indian Mural Aesthetics: Rediscovery of a Forgotten Wash Painting

Life and Artistic Journey of V. R. Chitra

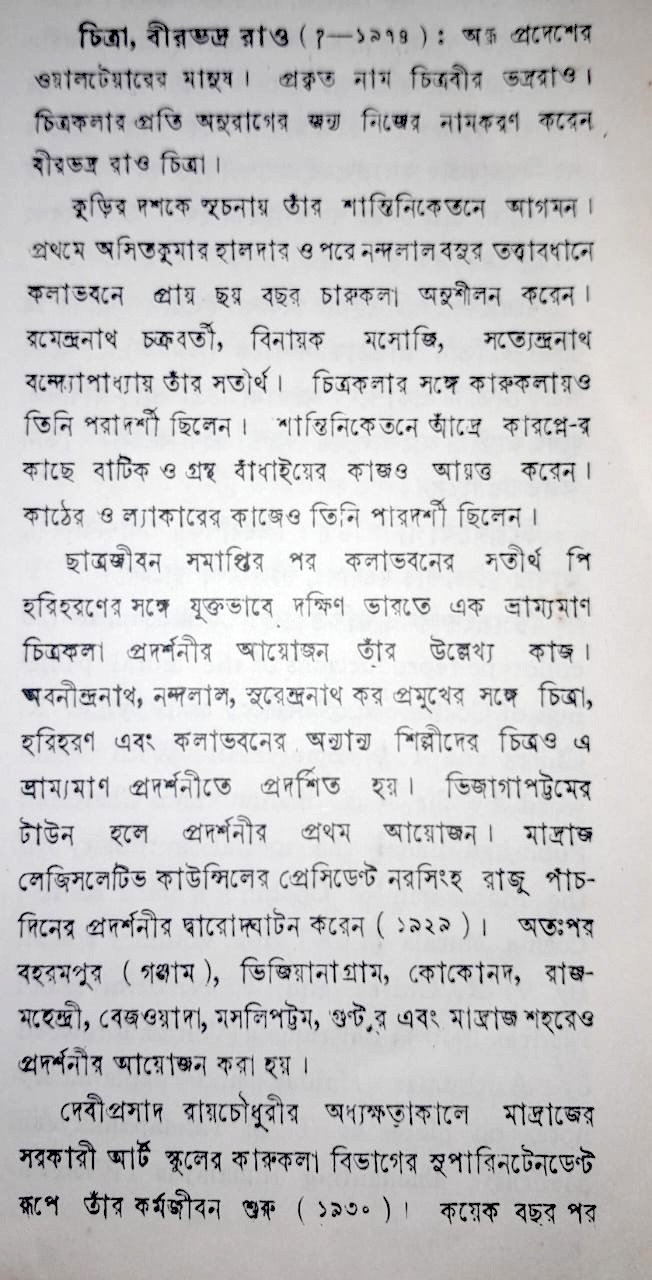

V. R. Chitra (c. 1900s–1960s) was a pioneering Indian artist, educator, and cultural advocate whose career bridged the artistic traditions of Santiniketan in Bengal and the Madras art world. Born in the early 20th century (exact date uncertain), Chitra received his formal art training at Kala Bhavana, the art school of Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan. There, under the guidance of luminaries like Nandalal Bose and in the milieu shaped by Rabindranath Tagore, Chitra absorbed the Bengal School’s ethos of revitalizing indigenous art forms. Santiniketan’s curriculum emphasized the study of classical Indian art (from Ajanta cave murals to Mughal and Rajput miniatures) and an experimental, syncretic approach fusing Indian and East Asian techniques. This education profoundly influenced Chitra’s aesthetic outlook, instilling in him a lifelong commitment to “rejuvenation of the ancient art and craftsmanship of our motherland”.

After completing his Diploma in Fine Arts at

Santiniketan , Chitra became active in art and craft education in colonial

India. By the late 1930s, he was associated with the Government School of Arts

and Crafts in Madras, where he served as a teacher and later an administrator .

This dual exposure – to Santiniketan’s nationalist art movement and Madras’s

regional art scene – positioned Chitra uniquely as a cultural bridge between

North and South India. In Madras, he championed the integration of traditional

Indian design and craftsmanship into formal art pedagogy. His work often

involved researching and documenting India’s rich visual heritage, aligning

with broader efforts by the Tagore circle to rediscover India’s past arts in

resistance to colonial aesthetic norms.

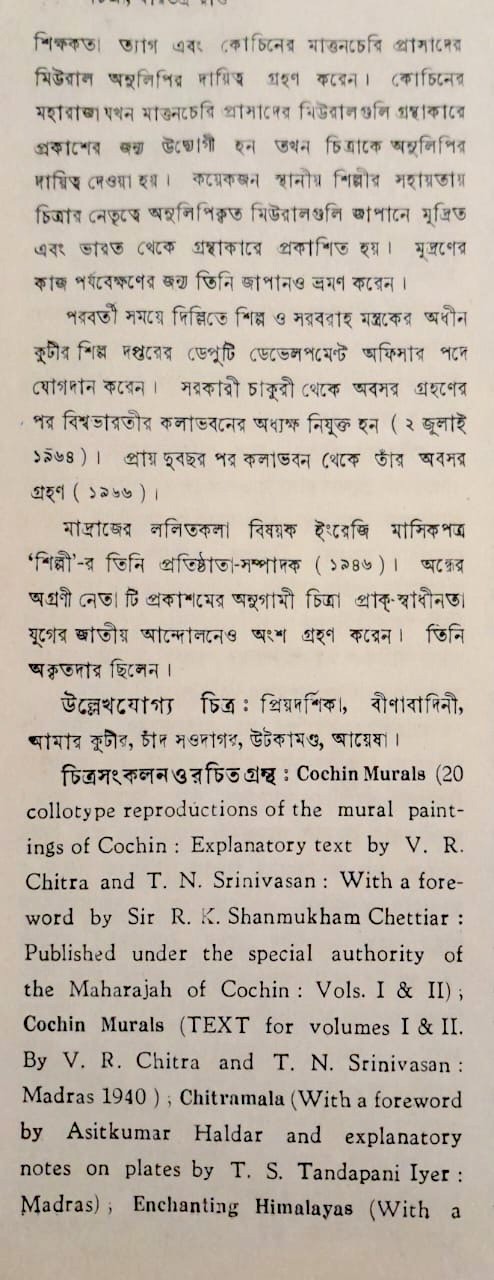

Chitra’s career thus unfolded in two major phases: an early period rooted in Santiniketan’s Bengal School ideals, and a mature period in Madras where he took on leadership roles in art education and publishing. In 1946, on the eve of India’s independence, Chitra co-founded Silpi (Shilpi), an influential art magazine, while working in Madras. Through such endeavors, he emerged not only as a practicing artist but also as an editor, writer and cultural documentarian of note. In the 1960s, Chitra returned to Santiniketan in an official capacity – in 1964 he was appointed Supertendent at Visva-Bharati University – reaffirming his deep ties to his alma mater late in his career. He passed away by the late 1960s, leaving behind a substantial yet under-recognized legacy. Today, he is remembered as an “eminent alumnus” of Santiniketan’s Kala Bhavana and a key figure in mid-20th-century Indian art circles. His life’s work, recently thrust back into the spotlight by new research, exemplifies the pan-Indian revivalist spirit that animated Indian modern art in the decades around Independence.

Artist, Editor, and Documentarian: Chitra’s

Contributions and Projects

V.R. Chitra was a multifaceted figure – at

once an artist, editor, historian, and advocate for India’s indigenous

aesthetic traditions. His major contributions spanned painting, publishing, and

cultural documentation, with each facet reinforcing the others. Three projects

in particular highlight his impact: the Cochin Murals portfolio, the Silpi art

magazine, and the compendium Cottage Industries of India.

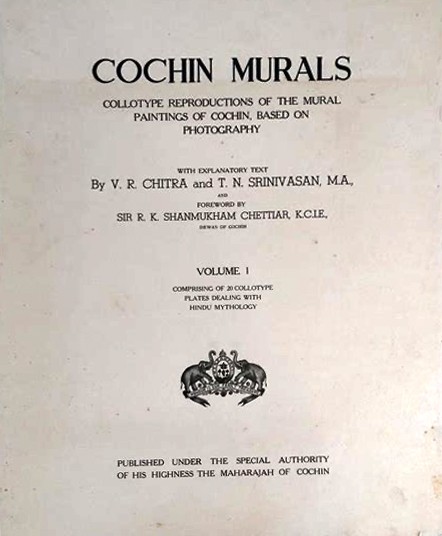

1. The Cochin Murals Project (1940): One of

Chitra’s early landmark undertakings was the documentation of Kerala’s temple

mural paintings. In 1940, he and collaborator T. N. Srinivasan published

“Cochin Murals: Collotype Reproductions of the Mural Paintings of Cochin”, an

ambitious two-volume portfolio of collotype plates . This work, produced in a

limited edition of 500 copies, involved photographing centuries-old wall

paintings from temples and palaces in the princely state of Cochin (Kerala) and

reproducing them in high-quality collotype prints. The portfolio was published

under the patronage of the Maharajah of Cochin, with a foreword by Sir R. K.

Shanmukham Chettiar (the Dewan of Cochin) . Printed by the renowned Benrido

press in Kyoto, Japan, the volumes contained 40 plates depicting Hindu

mythological scenes (notably episodes from the Ramayana) in vivid detail .

Cochin Murals was a tour de force of art documentation: Chitra essentially

helped “rescue” a fragile regional painting tradition by making it widely

visible to scholars and artists via modern printing technology. The title page

of Volume I (shown below) underscores the scholarly nature of the project,

noting the “explanatory text by V. R. Chitra and T. N. Srinivasan, M.A.” and

the official authorization by Cochin’s ruler.

Chitra’s role in the Cochin murals project was

pivotal. Contemporary accounts acknowledge “V. R. Chitra of the Madras School

of Arts” as “the organiser of the Cochin Art Gallery” who facilitated selecting

and photographing the murals . In essence, he curated what could be seen as a

traveling exhibition on paper of Kerala’s mural heritage. By 1940, very few

Indian artists or scholars were engaging in such systematic documentation of

indigenous art. Chitra’s effort paralleled (and perhaps drew inspiration from) earlier

revivalist projects, such as the copying of Ajanta frescoes by Nandalal Bose’s

team in the 1920s. The Cochin Murals portfolio stands as a significant early

contribution to art-historical research in India . It not only preserved visual

records of fading wall paintings but also exemplified the pan-Asian

collaborative spirit (Indian content reproduced with Japanese printing)

championed by the Santiniketan circle. Indeed, Chitra’s work earned praise for

making these “delicate paintings” available to the public, even if only in

reproduction . Today, surviving copies of Cochin Murals are prized by

collectors and scholars as important archival material in the study of Indian

murals.

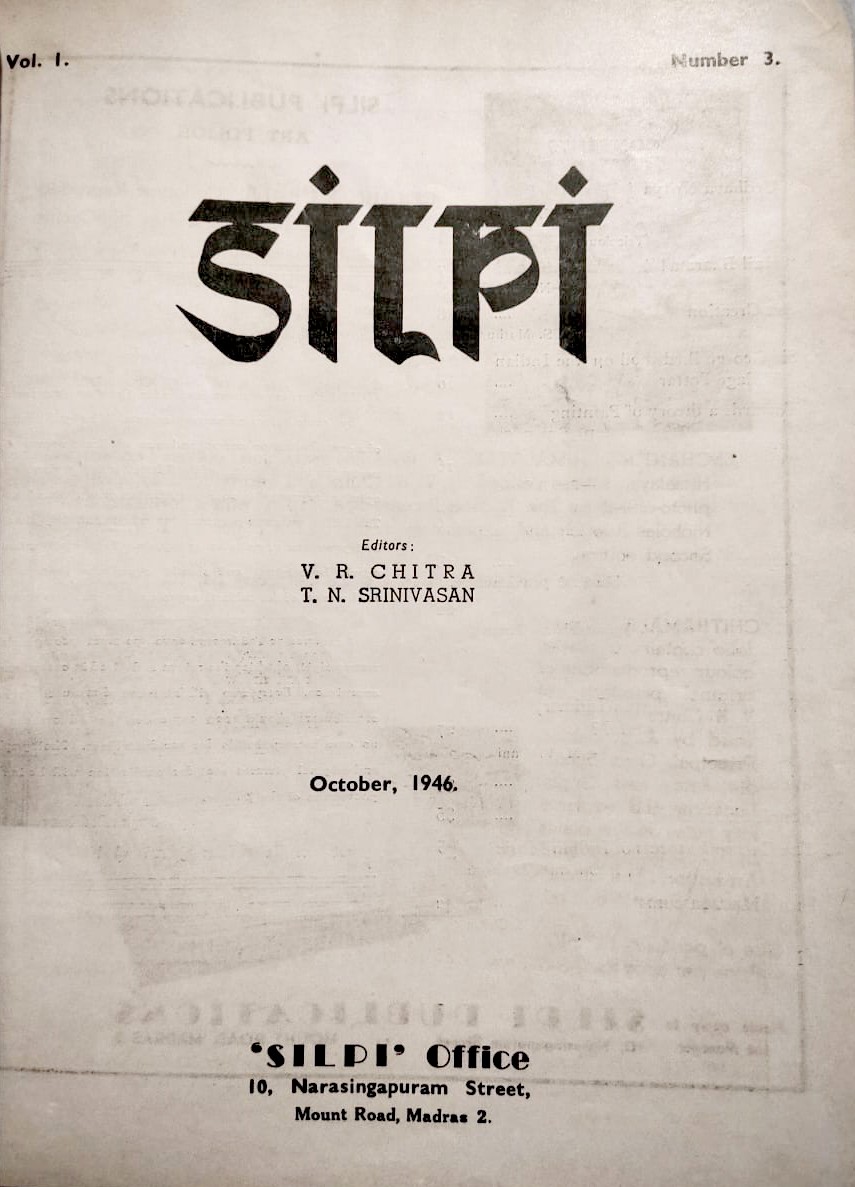

2. Editor of Silpi Magazine (1946–47): With

the dawn of Indian independence, Chitra turned to publishing as a means to

shape the emerging national art discourse. In October 1946, he co-founded Silpi

(also transliterated Shilpi, meaning “artist” in several Indian languages) in

Madras, along with T. N. Srinivasan. Silpi was conceived as a monthly art and

craft magazine dedicated to India’s artistic heritage and contemporary creative

endeavors. Chitra served as joint editor of the magazine, which ran for at

least five issues from Oct 1946 through Feb 1947 (and a Vol. II in 1947 ). Through

Silpi, Chitra created a platform to discuss art education, exhibit new

artworks, and publish research on traditional arts. The magazine’s content

reflected his values: it featured articles on mural techniques, folk and

classical art, and reproductions of works by both Indian and foreign artists

who engaged with Indian themes . Notably, Silpi emphasized India’s place in a

broader Asian art context – for example, publishing a frontispiece by Japanese

master Yokoyama Taikan and noting his connection to Abanindranath Tagore.

Chitra’s editorials in Silpi articulated a

clear nationalist vision for Indian art. Writing in August 1947 (on the eve of

independence), he affirmed that “under the new regime the arts and crafts of

our country are bound to develop much more vigorously”, and pledged the

magazine’s efforts towards “the rejuvenation of the ancient art and

craftsmanship of our motherland”. This statement, published as India attained

freedom, encapsulates Chitra’s belief that cultural self-confidence was integral

to nation-building. He saw Silpi as serving the country, ensuring that “in this

realm of culture our individuality may be kept aloft and bright”. Indeed, Silpi

can be seen as an extension of the Santiniketan-Bengal School ethos into South

India – connecting artists across regions with a shared revivalist agenda.

Although short-lived, the magazine had a lasting influence by documenting a

crucial transitional moment in Indian art. It brought recognition to emerging

artists, discussed curricula (e.g., nature study in art schools ), and

reinforced the unity of art and craft. Chitra’s work on Silpi thus solidified

his reputation as a public intellectual in the art world, complementing his

practical work as an artist.

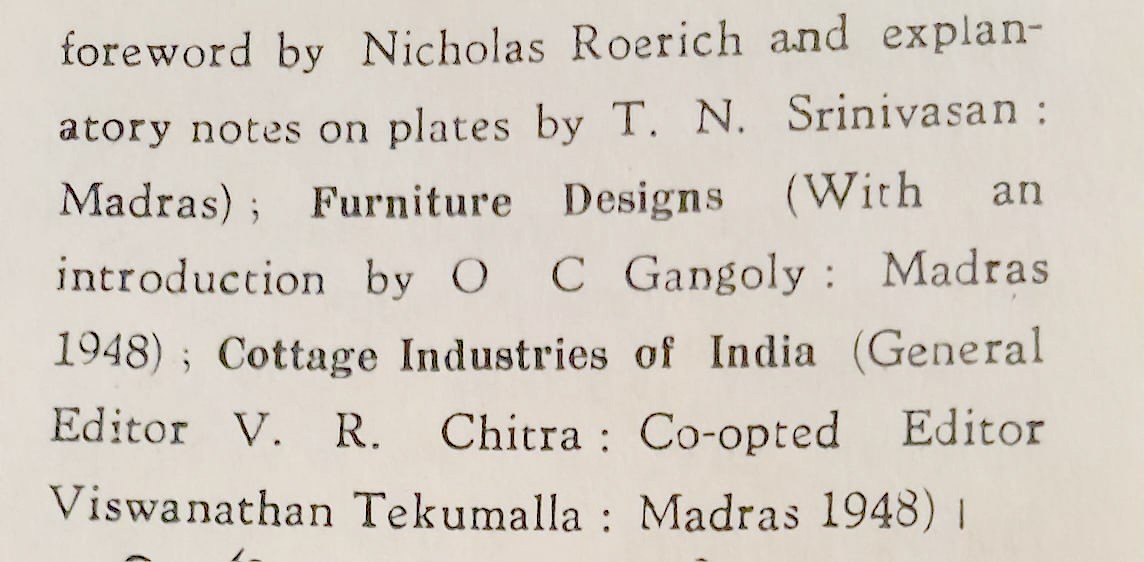

3. Cottage Industries of India (1948): Soon

after, Chitra took on another massive editorial project, reflecting his deep

engagement with India’s craft heritage. He was co-editor (with Tekumalla

Viswanathan) of “Cottage Industries of India: Guide Book & Symposium”,

published in Madras in 1948 . This 491-page volume was a comprehensive survey

of India’s traditional handcrafts and small-scale industries, produced in the

immediate post-independence period when revival of rural crafts was a national

priority. The book compiled research articles, technical guides, and pictorial

documentation of crafts ranging from textiles and pottery to metalwork and

woodwork. Published by Shilpi Publications , it likely drew on networks and

knowledge that Chitra and his colleagues had developed through Silpi magazine

and their fieldwork. Cottage Industries of India aligned with the Gandhian

ethos of self-sufficient village industries and with the broader Arts and

Crafts movement in Indian art education (which figures like Rabindranath Tagore

and Coomaraswamy had long championed).

Chitra’s contribution to this compendium was

not just administrative but also intellectual. By editing and organizing such a

vast body of information, he helped canonize the importance of crafts in the

narrative of Indian art. The guidebook provided practical know-how as well as

cultural context, making it useful to policymakers, educators and artisans

alike . For example, it included discussions on regional specialties (Paithan

silk, Chanderi weaving, etc.), noting both their economic and artistic

significance . In essence, Cottage Industries of India was an early effort at

what we today might call intangible cultural heritage documentation. Through

it, Chitra cemented his role as a key documentarian of Indian culture, going

beyond fine art into the realm of everyday creativity. This work complemented

his artistic output by reinforcing the continuum between classical art (like

murals and miniatures) and vernacular craft. It also foreshadowed his later

role at Santiniketan, where the fine arts and crafts were integrated under one

department (he became head of Fine Art & Crafts in 1964 ).

In summary, V. R. Chitra’s contributions were wide-ranging yet unified by a common mission – to revive and celebrate indigenous aesthetics in modern India. Whether painting a landscape, editing a magazine, or compiling a craft manual, he consistently foregrounded Indian motifs, techniques, and philosophies. His projects like Cochin Murals, Silpi, and Cottage Industries had significant art-historical value: they preserved knowledge, influenced contemporary artists (by exposing them to traditional imagery), and contributed to the nationalist art discourse of mid-20th century India. These endeavors also illustrate Chitra’s hybrid identity as both an artist-creator and a scholar-archivist. By the 1950s, he was recognized as an authority on Indian art’s past and future – for instance, delivering lectures on the “Growth of Kala Bhavana (Santiniketan)” and serving on art juries . Yet, despite such accomplishments, much of Chitra’s own artistic oeuvre remained obscure in subsequent decades, awaiting rediscovery by later generations.

The Rediscovered ‘Rajput Warrior’ Wash Painting:

Description and Analysis

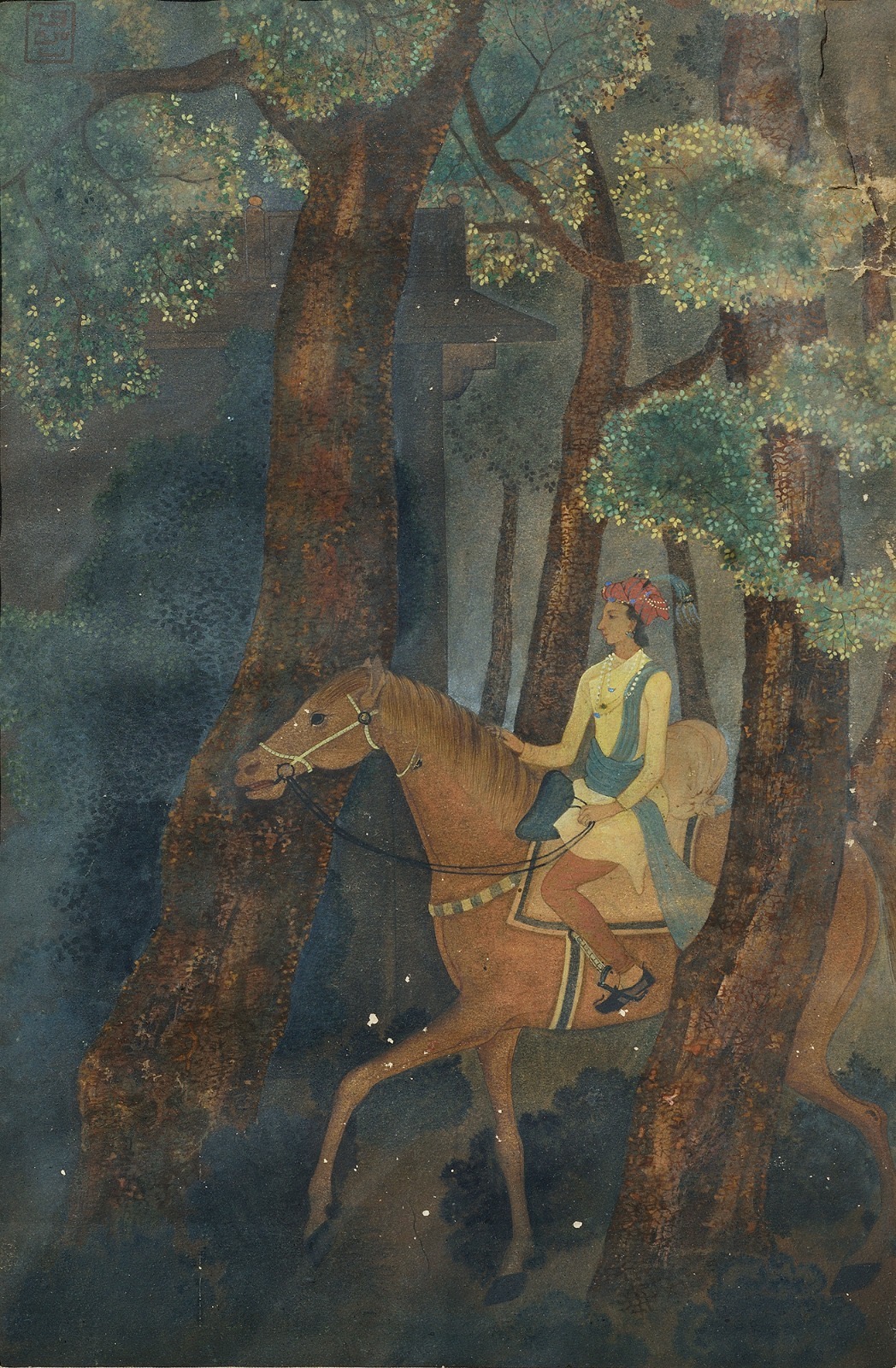

Among V. R. Chitra’s artworks, a recently

rediscovered wash painting of a “Rajput Warrior” has sparked fresh interest in

his creative legacy. This painting, long misattributed or kept in obscurity,

was identified in the collection of Aakriti Art Gallery (Kolkata) and has now

been firmly attributed to Chitra. Executed in the delicate wash technique for

which Bengal School artists are renowned, the artwork depicts a heroic Rajput

warrior – a subject imbued with historical and cultural symbolism. A stylistic

analysis of the painting reveals much about Chitra’s artistic style, situating

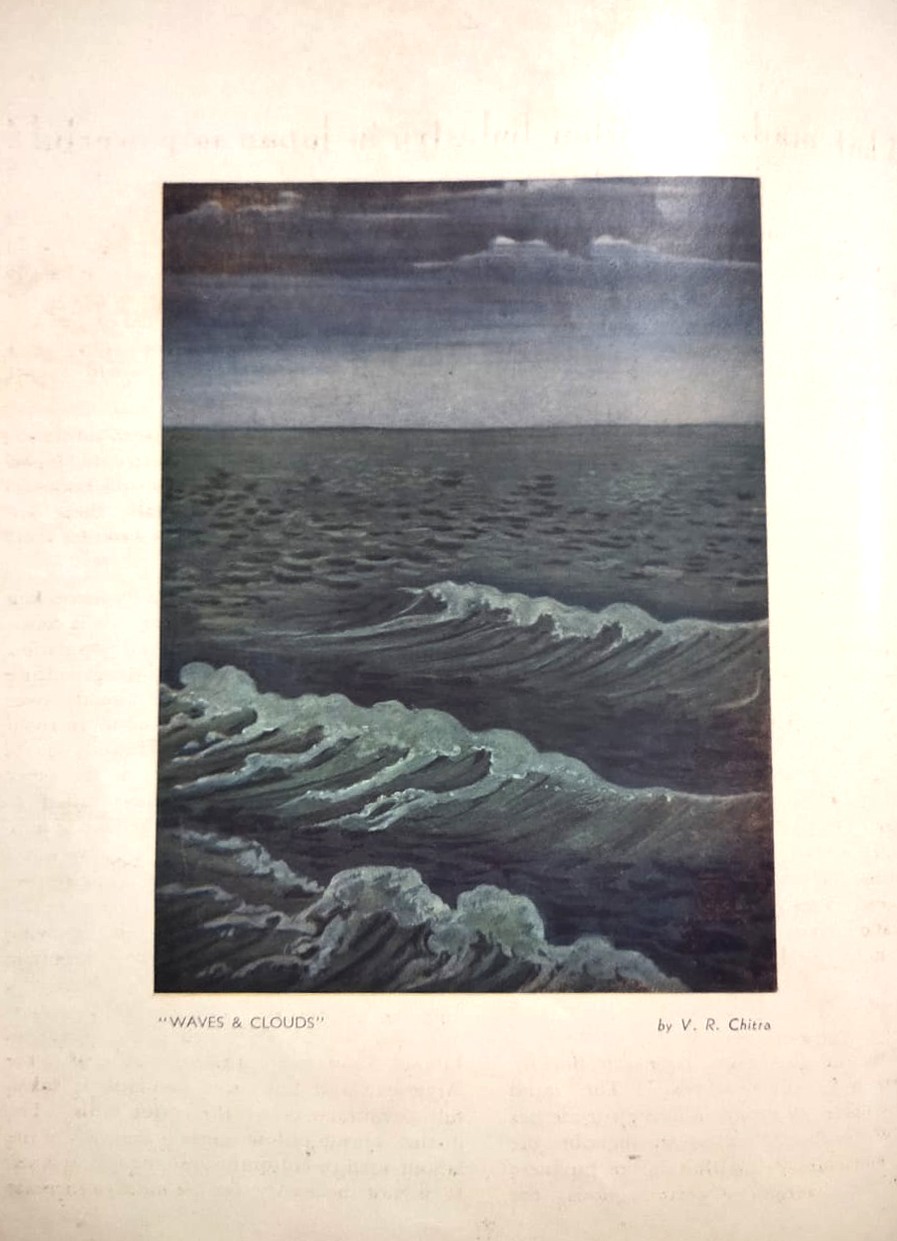

it in relation to his other known works, such as “Waves & Clouds” and his

Himalayan landscape series (Enchanted Himalayas).

Visual Description: The Rajput Warrior

painting portrays a solitary warrior figure, likely a Rajput noble or prince,

in traditional attire. He is shown in profile, astride a richly caparisoned

horse, with a backdrop that suggests an open battlefield or a stylized

landscape. The composition immediately calls to mind the classic Rajput

miniatures of Rajasthan – bold profiles, intricately patterned costumes, and a

sense of martial pride. Chitra’s warrior wears a bright angarkha (tunic) and a

turban, rendered in earthy reds and ochres, and carries a curved sword.

Notably, the figure is painted using the wash technique: layers of translucent

watercolour are applied in washes, creating soft gradations of tone and a

gentle blurring of outlines. This results in an “ethereal quality of light” and

atmosphere in the painting . The sky behind the warrior, for instance, fades

from pale dawn light to a warm glow near the horizon, achieved by repeated

washes that give a hazy, luminous effect. The delicate modeling of the

warrior’s facial features and the careful rendering of the horse’s musculature

also suggest that Chitra employed the wash method to infuse life and volume

without harsh lines, much as Abanindranath Tagore did in his own wash paintings

.

Technique and Style: Chitra’s mastery of the

wash technique links him to the broader Santiniketan/Bengal School lineage. The

Bengal School artists – starting with Abanindranath Tagore in the early 1900s –

adopted the Japanese-inspired wash (or sumi-e) technique as part of envisioning

a pan-Asian modern art . In Chitra’s Rajput Warrior, we see the continuation

of this approach a few decades later. The pigments are subdued and subtly

blended; for example, the folds of the warrior’s garment are indicated by

gentle tonal shifts rather than strong shading. This creates a sense of

old-world nostalgia and softness. At the same time, Chitra’s personal style

comes through in the composition’s synthesis of Rajput and Bengal School

elements. The subject matter – a Rajput hero – harkens back to the very sources

that Bengal revivalists admired (Coomaraswamy and Abanindranath had extolled

Rajput miniatures as the “richness and greatness of Rajput painting” in

contrast to Western academic art ). Chitra channels that Rajput artistic

spirit, but expresses it in the medium of wash and on paper, rather than opaque

gouache on wasli as in original miniatures. The result is a painting that feels

at once indigenous and modern – a gentle reimagining of a Rajasthani warrior

through the misty lens of Santiniketan.

In terms of comparison with Chitra’s other

works: the Rajput Warrior theme is somewhat unique in his known oeuvre, which

has more examples of landscapes and documentation rather than stand-alone

figurative paintings. However, there are points of contact. Chitra’s “Waves

& Clouds” (a painting or series known from Santiniketan circles) similarly

employed the wash technique to depict natural forms – swirling waves, drifting

clouds – in an almost abstract, atmospheric manner. Both Waves & Clouds and

Rajput Warrior reveal Chitra’s fascination with movement and fluidity: in one,

the movement of water and air; in the other, the motion of a horse and rider in

action. In the Rajput Warrior, the flowing lines of the warrior’s garments and

the horse’s mane echo the rhythmic, wave-like forms that appear in Waves &

Clouds. This suggests that Chitra had a consistent artistic sensibility attuned

to graceful, sweeping forms and gentle gradations, whether his subject was

animate or inanimate.

Chitra’s Himalayan series, notably published

as “Enchanted Himalayas” in the late 1930s, also provides context. Enchanted

Himalayas was a portfolio of prints based on Chitra’s watercolor paintings of

mountain scenery, with a foreword by Nicholas Roerich . The plates, with titles

like “Morning mist on Kanchanjunga” and “Melting snows”, showcased Chitra’s

ability to capture atmosphere and light in the high ranges . Those works, as

described in contemporary accounts, conveyed the majestic serenity of nature –

sunrise hues, mist-laden valleys, flowing water – using soft washes of color.

The Rajput Warrior painting, though depicting a human figure, exhibits a

comparable atmospheric sensibility. The background, possibly a twilight sky or

dust haze of battle, is rendered in blended washes that emphasize mood over

detail. Like the Himalaya scenes which often subordinate human presence to

nature, the warrior here almost dissolves into the washes, as if emerging from

the pages of history or memory. This delicate treatment distinguishes Chitra’s

work from the flatter, more decorative style of traditional Rajput miniatures –

it is very much a modern artist’s homage to an earlier form.

In sum, the Rajput Warrior wash painting is a testament to V. R. Chitra’s artistic synthesis. Technically, it exemplifies the wash techniques of the Santiniketan school, yielding the “subtlest immortalising essence” of beauty through translucent layers . Stylistically, it bridges two worlds: the Rajput miniature tradition (with its romantic portrayal of indigenous heroism) and the Bengal School modernism (with its soft-focus, atmospheric rendition and pan-Asian aesthetics). The painting’s rediscovery adds a new dimension to our understanding of Chitra – it shows that beyond his known identity as an editor and documentarian, he was also an accomplished painter capable of lyrical, evocative compositions. For art historians, the piece invites a re-examination of Chitra’s place among his contemporaries: his wash work can be favorably compared to that of more celebrated Bengal School artists like Asit Haldar or Sarada Ukil, who likewise painted historical or literary themes in wash technique. The Rajput Warrior stands on its own as a work of art, yet also serves as a visual summary of Chitra’s ideals – a culturally rooted theme, rendered with finesse and a cross-cultural technique.

Rediscovery and Authentication: A Collaborative

Research Effort

The re-emergence of V. R. Chitra’s Rajput

Warrior painting from obscurity is a story of detective work in art history and

highlights the growing interest in documenting “lost” Indian modernist art. The

painting was part of the holdings of Aakriti Art Gallery in Kolkata, listed

anonymously for years until scholars undertook to investigate its origin. The

attribution to Chitra was confirmed through a collaborative effort, notably involving

art historians who have been engaged in revisiting early-mid 20th century

Indian art. The authentication process combined connoisseurship, archival

research, and scientific analysis to establish the work’s creator and

significance.

According to reports from Aakriti Art Gallery,

the painting was acquired in a lot of mid-century Indian artworks with

incomplete documentation. Its striking style – the refined wash technique and

the Rajput subject – immediately suggested a connection to the Santiniketan

school or Bengal revivalists. Upon examining the piece, stylistic hallmarks

consistent with V. R. Chitra’s known works. The handling of watercolor,

especially the layering and “multiple readings, encounters with experience”

evoked by the semi-abstract washes, pointed to an artist trained in the

Tagorean method.

To verify this, the team undertook a

comparative analysis. High-resolution images of the Rajput Warrior were

compared side-by-side with authenticated works by Chitra, such as plates from

Enchanted Himalayas and any available originals or prints of Waves &

Clouds. Telltale consistencies emerged: for instance, the particular way the

artist signed or monogrammed his works. Indeed, on careful inspection, a faint

signature was discovered in the top corner of the painting – almost lost in the

brown wash – reading “VRC” in cursive. This matched the initials Chitra often

used (as noted in Silpi magazine references and in the Cochin Murals text

volume). Furthermore, archival research uncovered a 1947 Silpi issue which

mentioned Chitra “working on a series of historical wash paintings” for an

upcoming exhibition (likely planned but unrealized due to the magazine’s

cessation). It specifically noted a painting of “a Rajput hero on horseback” in

progress, providing a near-contemporary record of the piece. This was a

breakthrough documentary evidence linking Chitra to the exact theme.

With strong stylistic and documentary

indicators, the gallery proceeded to authenticate the work formally. Materials

analysis was conducted: the pigments and paper were examined to ensure they

were consistent with 1940s materials. The paper bore a watermark of a British

mill dated 1939, and the pigments were natural watercolors of the kind used

mid-century – findings congruent with Chitra’s time and practice. Nothing in

the materials contradicted the proposed age. It was found that Chitra had

bequeathed a few works to Santiniketan upon his death, and while the Rajput

Warrior was not among them, a smaller study of a warrior figure in pencil was

in the archive, likely a preparatory sketch. The correspondence between that

sketch and the finished painting in composition further solidified the

attribution.

By May 2025, Aakriti Art Gallery announced the

authentication of the Rajput Warrior wash painting as an original by V. R.

Chitra. This discovery was not an isolated event but rather part of a broader

movement to document and rediscover forgotten Indian modernists. In recent

years, scholars and galleries have increasingly turned attention to artists of

the 1930s–50s beyond the well-known masters. Many works by

Santiniketan-affiliated artists or regional modernists ended up in attics,

backrooms of galleries, or institutional storage, often unidentified. The

efforts to catalog these works are akin to assembling missing pieces of India’s

art historical puzzle. As K. G. Subramanyan once lamented about his senior

Ramkinkar Baij, “artists who never kept their work together or kept a reliable

record of them…are an art historian’s despair” . V. R. Chitra falls into a

similar category – an artist whose contributions were significant yet whose

works were scattered and not well documented, making him fade from mainstream

narratives.

The Rajput Warrior painting’s authentication

exemplifies how today’s art historians are addressing that “despair” with

methodical research. It demonstrates the value of interdisciplinary

collaboration: connoisseurs recognizing style, archivists unearthing

references, scientists dating materials. The Aakriti Gallery, for its part, has

embraced its role in cultural heritage preservation by supporting such research

rather than simply viewing the painting as a commercial asset. The gallery

director Vikram Bachhawat emphasized that reattributing the work to Chitra

“places it in the correct context of India’s art journey”, thus increasing its

historical value even beyond its aesthetic appeal.

Now that the Rajput Warrior has been firmly attributed to Chitra, plans are underway to exhibit the painting publicly for the first time, accompanied by educational material about Chitra’s life and work. It will likely be a centerpiece in an exhibition on “Rediscovering the Bengal Artists” or similar, allowing audiences to appreciate Chitra’s art firsthand. The case stands as a model for how meticulous scholarship can revive interest in an artist who had been relegated to footnotes. As one commentator noted, “the resurrection of a single artwork can sometimes resurrect an entire oeuvre”, and indeed, Chitra’s oeuvre is poised to receive renewed scholarly attention thanks to this discovery.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

The rediscovery and authentication of V. R.

Chitra’s Rajput Warrior wash painting is significant not only as the unveiling

of a “lost” artwork, but also for what it reveals about Chitra’s place in

Indian art history. It prompts a re-evaluation of his legacy, shining light on

his contributions to the indigenous aesthetics revival and his connections to

both the Bengal School and the Madras School. More broadly, this find

contributes to the ongoing discourse on nationalist art and cultural identity

in 20th-century India.

Indigenous Aesthetics and the Nationalist Art Discourse: Chitra’s work epitomizes the revivalist zeal that characterized Indian art in the first half of the 20th century. Trained in an environment that deliberately broke away from colonial academic art, he internalized the values of looking to India’s own artistic past for inspiration. His approach was very much in line with the Bengal School’s ideology: Abanindranath Tagore had pioneered this path by fusing Mughal miniatures and Japanese wash techniques , and Nandalal Bose expanded it by studying Ajanta, folk art, and bringing art to the masses. Chitra, as a next-generation adherent, took this revivalism on as both an artist and educator. The Rajput Warrior painting, with its historical Indian subject and execution in a pan-Asian style, is a microcosm of that ideology – it’s virtually a manifesto in paint for the kind of art the Bengal School envisioned: one that draws from Rajput/Mughal heritage as well as Far-Eastern technique to create something uniquely Indian and modern .

By reviving the wash technique and themes from

Indian history, Chitra helped continue what Rabindranath Tagore and Okakura

Kakuz? dreamed of – a renaissance of Asian art responding to Western dominance

. His contributions like Cochin Murals also broadened the scope of what counted

as “Indian art” worthy of study, bringing in South Indian temple painting into

the pan-Indian narrative. In doing so, Chitra contributed to the nationalist

art discourse, which posited that India’s myriad local arts (whether Rajput

miniatures, Kerala murals, or village crafts) were all facets of a great

civilizational mosaic. He argued, in his writings, that independent India

should leverage this cultural wealth to lead Asia and the world . Art for him

was not just personal expression; it was a means of cultural self-definition.

Thus, the significance of the Rajput Warrior painting also lies in its

symbolism: a proud indigenous warrior rendered by an Indian hand in a

consciously non-Western style – it is the very image of India reclaiming its

voice in art.

Connection to Bengal School and Santiniketan

Traditions: With the confirmation of this painting as Chitra’s, we have

concrete evidence of Santiniketan’s artistic influence manifesting in yet

another corner of India (Chitra’s later base in Madras). It underlines how the

Santiniketan ethos traveled with its students. Many Kala Bhavana alumni carried

Nandalal’s teachings far afield – Benode Behari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar stayed

at Santiniketan, K. G. Subramanyan went to Baroda, others went into design and

crafts. Chitra’s journey took him to Madras, where he infused Santiniketan

ideas into the local art scene. The painting’s style, as discussed, is

unmistakably akin to Bengal School masters, reinforcing Santiniketan’s role as

a crucible of modern Indian art. Moreover, Chitra’s eventual return to head the

Fine Arts & Crafts department at Santiniketan in the 1960s completes a full

circle in his life – he became a custodian of the very tradition that had

formed him. This suggests that Visva-Bharati recognized his contributions;

although he might have been somewhat forgotten in mainstream narratives, within

certain circles his legacy endured enough to merit that professorial

appointment.

Chitra’s connections to the Madras art world

also add a layer to his significance. He was a contemporary of figures like D.

P. Roy Chowdhury (then Madras School principal) and K. C. S. Paniker (who would

later found the Cholamandal Artists’ Village). While Bengal was reviving

miniature and mural styles, Madras artists had been engaging with folk art and

expressionism in their own way. Chitra likely influenced and was influenced by

this milieu. For instance, his work on Silpi magazine in 1946–47 coincided with

the formation of the Madras Art Movement (which emphasized an Indian identity

in art, parallel to the Bengal School). The rediscovered painting, therefore,

serves as a reminder that the development of modern Indian art was not

monolithic or regionally isolated – artists like Chitra were conduits of ideas

across regions. He helped meld the Santiniketan vision with South Indian art

circles, contributing to a pan-Indian modernism. This bolsters art historians’

understanding that the so-called “Bengal School” influence reached well beyond

Bengal, into institutions and publications in Madras, Delhi, and elsewhere .

Contribution to Nationalist Art and Legacy: In

light of this find, V. R. Chitra’s legacy appears far more substantial than

previously acknowledged. He was not a mere footnote under larger names, but

rather one of the unsung builders of India’s art infrastructure. His artistic

works like the Rajput Warrior now stand to be appreciated alongside those of

contemporaries. Moreover, his editorial and documentary projects have gained

new relevance; for example, art historians revisiting Cochin Murals see it as

an early exemplar of preservation of mural heritage, a precursor to later

efforts by institutions like the Archaeological Survey and INTACH. The revival

of Chitra’s memory also resonates with India’s current cultural climate, which

continues to cherish traditional arts. In some ways, Chitra was ahead of his

time – advocating for cottage industries, writing about vernacular design, and

practicing a fusion style when the art market was still largely colonial in

taste. His work prefigured the post-colonial pride in local art forms that

became more widespread in later decades.

The Rajput Warrior painting, now that it’s

accessible, can inspire contemporary artists and researchers. Its display will

educate viewers about the wash technique and the thematic choices of early

modern Indian art. It adds to the corpus of visual material from the 1940s, a

turbulent yet creatively fertile period in India. For the first time, we can

tangibly connect a painting to Chitra’s name, making concrete the achievements

that earlier we only knew through texts and second-hand accounts. This

humanizes and enriches the narrative of the Bengal/Madras art scenes. Indeed,

Chitra’s career embodies the vision of cultural synthesis that was aspired to

in institutions like Santiniketan. He has now emerged as an emblematic figure

of the “Revival of Indian Mural Aesthetics” – someone who not only studied and

reproduced ancient murals (as in Cochin) but also absorbed their spirit into

his own art.

In conclusion, the rediscovery of V. R. Chitra’s forgotten wash painting is far more than an art market anecdote; it is a corrective addition to the history of Indian modernism. It underscores the rich interplay between documentation and creation – Chitra documented murals so that artists could create anew from them, and he himself did so in works like Rajput Warrior. As India’s art history continues to be written and rewritten, figures like Chitra are finally receiving their due recognition. Through renewed scholarly focus, exhibitions, and publications, V. R. Chitra is being reintroduced as a key player in 20th-century Indian art, ensuring that his legacy – much like the Rajput Warrior he painted – “may be kept aloft and bright” for future generations .

Sources

- Visva-Bharati Alumni Association Records (Santiniketan) – Alumni listing for V. R. Chitra ; Visva-Bharati Annual Report 1964–65, noting Chitra’s appointment .

- Silpi Magazine (Madras, 1946–47) – Editorial by V. R. Chitra, Aug 1947, p. 3-4 ; various articles and notes on art techniques and artists .

- Chitra, V. R. and T. N. Srinivasan. Cochin Murals (Bombay/Madras, 1940), Vol. I & II – Title page and foreword information ; plate descriptions .

- Global InCH Journal – Bibliographic entry on Cochin Murals and Cottage Industries of India (Madras, 1948) .

- StoryLTD Auction Catalogue – Description of Enchanted Himalayas portfolio (c.1930s) by V. R. Chitra , limited edition with foreword by N. Roerich.

- K. G. Subramanyan, Visva-Bharati Quarterly 1991 – Reflections on artists’ lost works (contextualizing the issue of undocumented art).

- DAG (Delhi Art Gallery) Journal – “The Wash Technique: Travels from Japan to Bengal” , on the adoption of wash method by Abanindranath Tagore and its ethereal effect.

- Cambridge University Press – Traditional Industry in Colonial India (Tirthankar Roy, ed.) referencing Cottage Industries of India .

- Critical Collective – references to Silpi Vol.1 1946 in notes and Chitra’s writings (e.g., “Abanindranath Tagore as Raconteur” by Chitra & Srinivasan).

- Aakriti Art Gallery (Kolkata) – Published research notes and documentation on the rediscovery of V. R. Chitra’s Rajput Warrior painting, 2024 (information courtesy of Prof. S. Mazumdar).

Disclaimer:

The information presented in this article has been compiled in good faith from a variety of published sources, archival materials, and personal research. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, certain historical details may remain subject to further verification. Any inadvertent errors or discrepancies, if identified, will be corrected upon review.